The train we took from Germany eastward to Budapest was the Orient Express – not the fabled train of Agatha Christie novels, but it still did hold a few adventures for us, both good and bad. It was exciting to see so many different landscapes and be swept through so many languages along the way. In fact, as we stumbled off the train in Budapest, a man approached Joe and asked, “Taxi?” Without thinking, he replied, “Danke, nein.”

Wrong language, clearly. But it was amusing.

On the other hand, we had some wild times trying to catch closely-scheduled trains with all our luggage despite our lightened load. As we’d found before, the stops were generally so short in duration that they could be downright nerve-wracking. The shortest was in Nürnberg, where we managed to make the switch in four minutes flat using our newly synchronized system of luggage off-loading.

However, it was in Vienna, where we had the longest stop – a full 20 minutes – that we had the hardest time of it. When we disembarked from our sleeping car – in which we’d done very little sleeping – our connection to Budapest was packed to the point of being overwhelming. I ended up running ahead, with Joe following behind, carrying as many bags as he could. Reuben we left alone on the platform guarding the remaining bags as we checked car after car without success.

Joe finally had no choice but to throw the luggage he held onto any old car and go back to get Reuben and the rest of our possessions. He had to run all the way there and then all the way to the car in question, our son on his heels even as the train slowly pulled out. I felt panicky during the whole maneuver and sat sweating in the crowded, non air-conditioned train car in the sweltering 90 degree heat.

However, that little drama wasn’t as striking as the act of crossing the border from Austria into the communist East Bloc. The seemingly simple geographical transition involved more theatrics than we dreamed possible: the stuff of fiction and movies. Crossing through the Iron Curtain.

As the train neared the frontier between the two countries, we could feel the mood palpably change. Our fellow passengers became tense and much quieter, and we soon realized why. The Austrian border patrol left the train at the appointed location, and the Hungarian border guards came crashing onto the train in their place. Gone were the polite guards with side arms. Instead, we were confronted by men with machine guns and large dogs, rudely rousting passengers, pulling up bench seats looking for hidden people and smuggled items and rooting through suitcases, including ours. During the 40-minute border stop, we sat in the airless compartment surrounded by the combined odors of sweat and raw onions from a passenger’s lunch, silently watching the armed guards inspecting the underside of the train with a mirror.

I remember thinking, “What have we done? Why did we decide to move to a police state?”

We did make it through the border crossing though, somewhat shaken and sincerely hoping to see a friendly face upon our arrival. In that, we weren’t disappointed. We were met at the rail station by the appointed couple we’d been told to expect, Peter and Maria Falley, who were holding a sign for “Miller Familie.” A German businessman in his fifties, Peter stood stiffly clutching his ubiquitous briefcase while Maria had soft Hungarian looks with dark brown eyes, a smart short coiffure and a stylish skirt.

Peter and Maria were very kind and wanted to help in every way, going above and beyond in an almost overprotective manner. We were very grateful to them, not only for the warm welcome they provided us but also for finding us an apartment in the historic Buda side of the city. They drove us up the hill in their Opel from the train station, past the peeling porticoes of the large villas that lined the street. As they informed us, these were once the homes of wealthy citizens, but they’d been nationalized in the early 1950s and divided into small state-owned flats after World War II by the newly empowered communist authorities.

We also learned that families who lived there – in fact, people who lived all across this new city of ours, with its two million residents – often shared both kitchens and bathrooms with other families.

The first thing we were required to do upon arrival was to register with the police in the district our new apartment was located. Entering a grey stucco building, the porter directed us to a small office where a policeman sat behind a beat-up desk. To his left on the wall hung a framed print of Vladimir Lenin.

We signed the forms slid our way, and he stamped each one multiple times with a flourish, clearly relishing his power by granting us the proper permissions to stay for three months. After that, we’d have to apply for a university student extension in order to get internal passports, which we’d be required to have with us at all times. All Hungarian citizens must carry this little booklet that listed every address, job and family member they had – yet another sobering reminder of life in a police state. As American citizens, we were still obligated to comply with their laws for Hungarians, including random ID checks by the police on the street. (photo below)

Our Flat

Peter and Maria took us to our apartment after that. It was situated on the Buda side of the Duna (Danube River) which was hilly and lush, with large shady trees. Quiet streets were lined with old stone villas and offered fresh air; the neighborhoods exuded a leafy suburban elegance. Just a bus ride up from Moszkva tér (Moscow Square), our Zugligeti ut was a wide street located away from the crowded center of the city.

Many of the lawns on either side featured knee-high weeds, and all the buildings were poorly maintained. The Communists were obviously terrible landlords. In a relatively brief 40 years, they’d managed to neglect the apartment buildings on Zugligeti ut and most grayish, elegant buildings elsewhere in the city. Despite this, ours must’ve been a desirable neighborhood because the Embassy of Canada was located just up the street from us and the American Ambassador’s residence was situated close by as well.

When we were shown inside our ground-floor flat, the accommodations did admittedly seem very small in comparison to our spacious farmhouse apartment back in Pennsylvania. It consisted of a small kitchen, a large living room – which doubled as a bedroom for Joe and me – a small bedroom for Reuben, and a bathroom with a tub but no shower.

There was also no air conditioning anywhere, which meant we were doubly blessed to be on the ground floor. Our best source of cooling was the tall set of double French windows that opened outward from the living room, thereby allowing air to circulate through it and the other rooms.

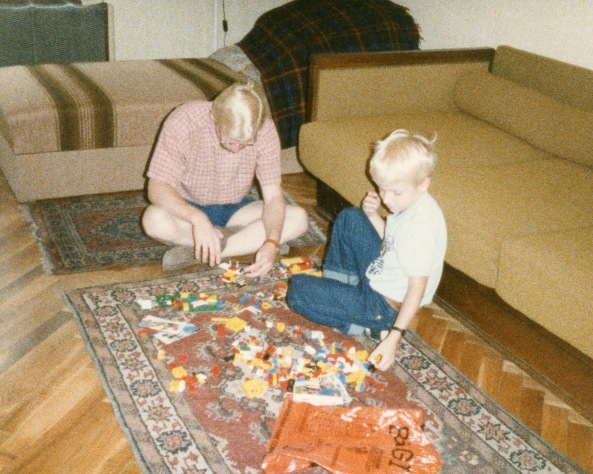

There were many striking and even beautiful aspects about the place, including the floor, which was fashioned in a herringbone pattern in oak parquet, then covered with several beautiful Persian carpets in rooms where the ceiling stretched 10 feet high. The whole apartment somehow exuded an atmosphere of decayed elegance. According to our new friends, they had found us a very nice place by local standards.

According to Hungarian regulations, we were also limited in where we could live – choices that were dictated by designated state agencies – and had to pay higher rent because of our foreign status. That was always taken care of with a stack of 1,000 forint bills, as the country was an entirely cash-based society at the time. By contrast, when the three of us stayed in Budapest for several weeks in 2015, I booked a flat online from a private family.

How incredibly much change had occurred in 30 years!

When we first arrived three decades ago, however, Reuben may have best described our new accommodations. When he wrote a letter to his grandparents, he mentioned how his room was about the size of a hallway – which it was – and how his parents slept in the living room – which we did. In Hungary at that time, housing was scarce in the city, so people put their children in the living room on a daybed during the night, then stored the bedding in a wardrobe the rest of the time. The Falleys thought this was more than adequate, not a problem at all. They were more focused on the fact that the flat had a phone.

What they failed to tell us, unaware that we’d find it odd, was that the neighbors all had a key to our flat because of that phone. They had tacit permission to use it when we weren’t there.

Talk about a culture gap!

The Phone

As it turned out, a phone was a major selling point in a country where only about 10% of households actually had one. Unlike in the U.S., Hungarians owned their phone lines and could take them with them when they moved. They were such hot commodities that it wasn’t uncommon to see apartment ads boasting their phone-line access… even though actual installment wasn’t scheduled for a full year or more into the future. Moreover, the lines could get waterlogged far too fast and too often, so it was close to impossible to call anyone when it was raining.

It was a running joke that the West Germans had requested to feature the Hungarian phone system as a museum exhibit, but the Hungarians declined. After all, they were still using it.

The only way we discovered the arrangement with our own phone was after Reuben got home from school one day before we arrived home. That’s when he found the front door open and a woman contentedly chatting on our hot commodity. We soon put a stop to that practice because we felt unsafe with others able to access our flat so easily. But it was definitely a lesson learned how privacy for Americans and privacy for Hungarians meant something very different.

In the people’s collective under Lenin and subsequent leaders, the private life was dead. So wrote Boris Pasternak in his popular novel, Dr. Zhivago. In communist society, the emphasis is on the community of workers rather than the rights of an individual.

That oddity aside, we caught on to the system quickly enough. Whenever we saw a long line of Arab students and other foreigners at a phone booth downtown, we knew the phone was “broken,” thereby enabling users to phone distant countries for free. What it did not ensure, however, was a clear connection. One time I tried a call to my parents and it was not very satisfying, and caused families to worry more than usual.